U.S. Government's Insolvency—

Not a Bad Thing

Some people today say that the United States government is bankrupt. It’s usually said in a negative way that suggests that this is catastrophic and that at some point everyone is going to wake up and realize that the emperor has no clothes.

What does it mean to be insolvent, and why is that necessary for a country to function in a modern monetary system? I admit, how it works can be somewhat mind-blowing. It took me a while to understand the principles behind it.

First, we'll look at what it means to be bankrupt. Being bankrupt assumes that a court of law has declared you bankrupt, unable to meet your debts. This is a legal designation.

We’re going to get away from that term here, and focus instead on insolvency. Merriam-Webster’s definition of what it mean to be insolvent is: either (a) unable to pay debts in the usual course of business, or (b) having liabilities in excess of a reasonable market value of assets held. It doesn’t have to be both. It can be one or the other.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office, or GAO, does an audit of U.S. financial statements every year, which they typically release in late February. The GAO audit of 2013, for example, showed that the United States had liabilities, or debts, of just under $20 trillion.

This debt was comprised primarily of $12 trillion of debt owed to the public, often called the national debt, and $6.5 trillion of benefits owed to federal employees and veterans. These are the two main liabilities.

What are the assets? The GAO estimated assets for the same year of $3 trillion, comprised primarily of $1 trillion of student loans receivable (most U.S.- students loans are issued and backed by the U.S. government). Much of the remaining $2 trillion of assets are property and equipment that the U.S. government owns—federal facilities such as the White House, the Capitol building, and other federal properties. (National parks and others national assets are not included in this asset mix.) Thus, under Merriam-Webster’s second definition, the United States is insolvent: its assets are worth significantly less than its liabilities.

Now usually when a business is insolvent, it’s creditors get worried. They move to collect the outstanding debt or refuse to lend additional funds. This places the business under Merriam-Webster’s first definition—unable to pay its debt. The business must move to borrow money or raise more revenue (i.e., equity capital). If an entity continues to lose money, then investors won’t lend it any more.

The government is not a business and is not looking to make a profit.

We don’t typically think of the U.S. government as suffering losses. But if in a year it receives less in taxes than it spends, then technically that’s a loss, and the government must cover the shortfall by borrowing money. The government has been suffering losses every year. So why haven’t its creditors refused to lend it money? They continue to lend at very low interest rates despite the government’s insolvency and ongoing losses.

Why Doesn’t the Government Break Even?

Why doesn’t the government run a surplus, achieve a profit, spend less than it gets in taxes, or at least break even?

It can’t. Here’s why: the government controls the expense side, but not the revenue side. Businesses and households control the revenue side.

Companies earn income (i.e. profit) by spending less than they receive in revenue. Profits are business savings, since by definition an entity saves when it spends less than its income. Companies pay a portion of their profit to the U.S. government in the form of taxes.

But here’s where it gets complicated.

Businesses get their income from other businesses and households that buy goods and services from them. Most households get their income by working, which is some company’s expense. Thus, a household’s income is an expense for some company.

To prevent losses and insolvency, businesses and households try to spend less than their income. If they do become insolvent, they will need other businesses and households to give them some of their savings, in the form of a loan or investment in equity capital.

If it sounds like we’re going in circles, we are. Here are three principles:

- Whenever a household or business spends a dollar, that dollar is someone else’s income.

- When a household or business lends or invests a dollar, they’re lending their savings.

- The only way households and businesses can save is to spend less than their income.

So if every dollar spent is someone else’s income, and if the only way to save is to spend less than your income, we have a downward spiral. The only way it works is if there is some entity willing to spend more than its income. There needs to be an entity willing to suffer a loss so that everyone else can save.

That entity is the federal government.

It suffers a loss by running a deficit. It doesn’t choose to do this. It is determined absolutely by households and businesses.

How is this so?

The federal government sets up a budget for the year, what it’s going to spend, and then hopes that the revenue comes in to allow it to run a balanced budget.

If businesses collectively try to increase their savings (i.e. boost their profits) by spending less, they do so by hiring fewer employees or laying off or firing employees, and by buying less from other businesses, which in turn effects those businesses’ income.

The result is lower incomes for both households (due to higher unemployment) and businesses (because they are spending less, creating less income for all businesses). Federal government tax revenue will fall because as a nation income is down, and the country winds up running a budget deficit.

Then the government, in order to balance its books, goes out and borrows money by issuing U.S. Treasury bonds and notes.

The fact that the federal government is insolvent is really just a function of having run deficits for many years, because the country’s businesses and households want to cut their spending or save.

At the end of the day, the federal government’s s excess spending over and above what it collects in taxes flows into the economy, boosting company profits, which means total savings actually increases to the level businesses and households desire.

The bottom line is, the U.S. government is insolvent because its debt greatly exceeds its assets and that debt represents decades of budget deficits that are a consequence of businesses and households desiring to save money. The government is not a business and is not looking to make a profit.

Banks and Trade

I’ve made some simplifying assumptions here. I’ve ignored trade. Countries that run trade surpluses (i.e., have businesses that export more than they import) are bringing in excess income, which households and businesses can save. Countries that run a trade deficit have households and businesses that are sending out money that potentially could be saved, which reduces the ability to save.

I’ve also not discussed banks. When businesses suffer losses, they technically borrow by raising capital or getting loans from other business and household savings, but in reality most lending is done by banks.

Banks do not have to collect deposits to make loans. Banks create money simply by the act of making a loan—that is what creates the deposit into the borrower’s account. If this sounds confusing, it is, but that is how it works.

The Federal Reserve, like the banks, can create money simply by, well, by creating it—the Fed effectively controls the money supply. It can cap interest rates and decide that it won’t pay any more than 3% interest, for example, and our central bank will buy as much debt as it needs in order to accomplish that.

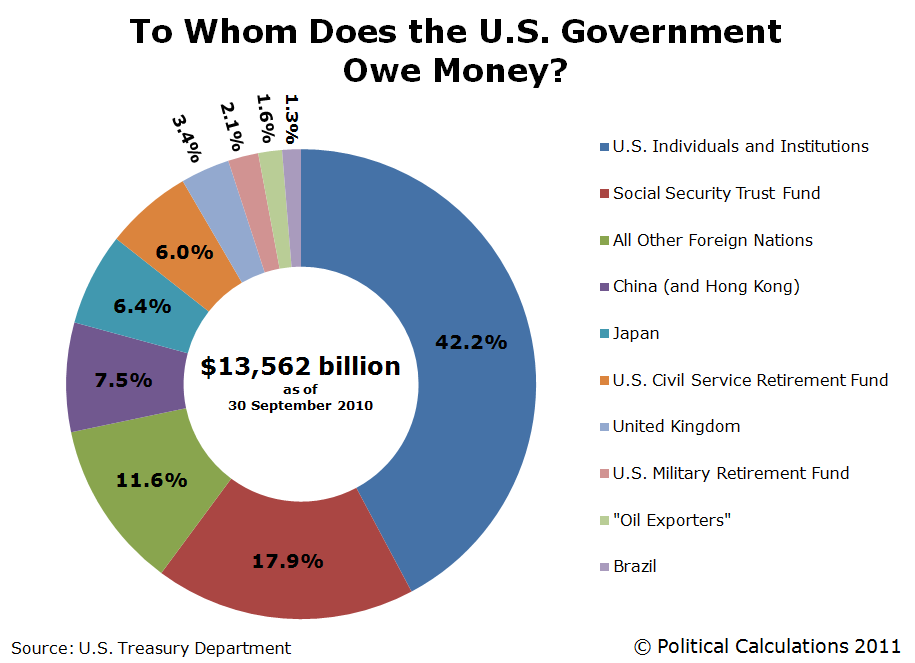

Whether we realize it or not, holders of the national debt —that would be foreign countries, businesses, you and I through mutual funds—believe that the U.S. government will pay its debt. We all believe we will get our principle back with interest; we continue to fund the national debt even though the government is technically insolvent.

What if everyone decides they no longer want to lend to the federal government? In that unlikely scenario the Federal Reserve would step in and buy government debt, just as it has through its quantitative easing program. It is unlikely because the U.S. government has been “insolvent” for over a century, and that hasn’t yet stopped investors from storing their savings in government bonds.

How Wealth Is Created

Ultimately, a nation’s gross domestic product, or GDP, is a measure of the value of the products and services of what the nation (primarily its businesses) produces. GDP is calculated, or estimated, in two ways: (1) total spending and investing within a country, or (2) total income, because a nation’s spending always equals its income.

The government cannot spend willy nilly, and it is not without constraints. What the government spends the money on is a matter of national policy and should be actively debated.

One question I get all the time is, what if China, which owns a large percentage of the national debt, decides that it doesn’t want to hold this debt any longer and then sells it all, dumps it all onto the market?

China owns the debt because as a nation we’ve bought so much stuff from them. We run huge trade deficits with China. We hand them dollars and they take those dollars and buy U.S. Treasuries.

One thing that could happen is that the Federal Reserve would step in and soak up that excess supply, buy all that debt.

Then what would China do with all that money? China could exchange the dollars in the foreign exchange market, which would increase the value of the yuan (the Chinese currency), which would hurt Chinese trade. Or, it could spend those dollars in the United States, buying up property, plants, goods, and services, which could push up the prices of everything, sparking inflation to the extent that our capacity to produce is limited against this huge inflow of money from China.

This is a concern and it’s why running huge trade deficits can be dangerous. Think about this for a moment. There’s a sentiment often stated that it’s the U.S. government’s fault that China owns so much of our debt. If the U.S. government wouldn’t run budget deficits, China wouldn’t own so much of our debt.

But the reality is that China owns debt because businesses, households, and individuals are making purchase decisions that result in a very large trade deficit with China, which then—we handed them the dollars and they have to do something with them—is choosing to buy U.S. government debt.

Even if we were running budget surpluses for many years, China would still be buying the debt and holding it, with interest rates potentially even lower.

The Deficit Is Not the Issue

The issue is not that the government is running a budget deficit. The percentage of foreign ownership of a nation’s debt is driven by business and household decisions regarding how much they want to save, what they want to buy, and whether they want to buy domestic-made or foreign-made goods. When a country runs huge trade deficits it potentially risks future inflation if another country that owns a large percentage of that debt decides to dump it on the market. The danger is that the other country may use the dollars it is cashing in on to buy up U.S. goods and services, which causes inflation because our capacity to produce is constrained.

The real wealth of a country is its ability to produce goods and services. This makes my head spin every time I write and talk about it. It is very, very, very circular, but that is how the monetary system works.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!