Lessons From the Yucatan

Many years ago I met a Mayan couple in the Yucatan who seemed incredibly happy. They were in their sixties, and they lived in an oval one-room house. The house walls were made of vertical sticks and covered with clay that had been painted white on both the interior and exterior. The roof had a steep pitch and was laid with thatch. There were no windows, just a front and a back door.

The main piece of furniture was a large handmade armoire where the couple kept their clothes and other valuables. There were a few chairs, a table, and two hammocks hanging on the wall that they would unfurl and stretch across the room for sleeping.

The only other large object in the room was a wooden frame with a partially woven hammock. Behind the house there were two outbuildings, a small kitchen and an outhouse.

This couple stood out from the many families I met in the Yucatan because they kept their house and yard in perfect order. Even their clothes were spotless—the lady of the house wore a brilliant white Mayan dress with colorful embroidered flowers, and her husband wore grey pants and a white guayabera shirt that, I learned, was usually left unbuttoned unless visitors came.

They earned money weaving hammocks, and I suspect they were incredibly poor. I ordered a custom hammock from them. A grandote is what they called it —one large enough for me. It took them over a month to finish it, and I have hauled this soft green bundle around with me from house to house for over thirty years.

Perhaps I was naïve in assuming they were happy. I don’t remember whether they had children or grandchildren. Maybe they were lonely. But the feeling I had as I sat in their house was that I could be happy living there with such simplicity and order.

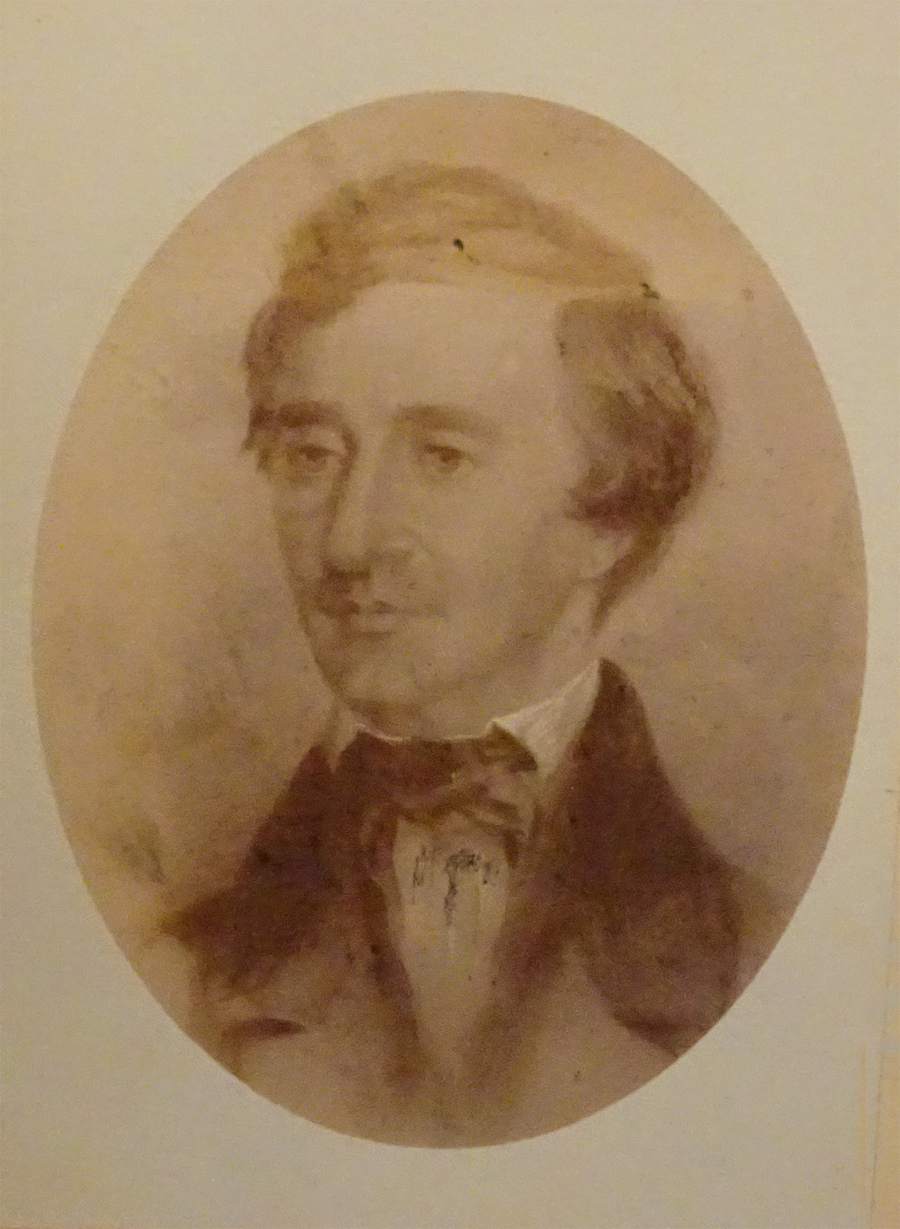

Henry David Thoreau wrote in Walden:

Most men appear never to have considered what a house is and are actually though needlessly poor all their lives because they think that they must have such a one as their neighbors have.

Clearly, the Yucatan couple who made me feel so at home did not have this pressure.

I often get emails from individuals who are in their fifties or sixties who have little savings. They worry how they will live in retirement. Many of them have lived fulfilling lives but haven’t given much thought to money, and now they must. My advice to these individuals is to live like you are already retired.

What do I mean? The couple I knew in the Yucatan didn’t think in terms of retired versus working. The social security program offered in Mexico at the time was so meager that most older couples continued working in some form. In this couple’s case, they wove hammocks. They lived a simple life. They owned their own home and kept their few belongings in perfect order.

Am I suggesting that the key to surviving into old age with little savings is to live destitute, in a one-room hut with an outhouse? No. I am suggesting that the term retirement is as much a mindset as an age, one that can allow us the freedom to choose those activities that are rewarding and bring us happiness. For many retirees, those activities will include work. But it needs to be less physically demanding work that we can sustain into our sixties, seventies, or even eighties.

I have a friend who went to dental school in his mid-forties with six kids still at home. This year he turns 50 and has little savings and a lot of debt. Yet, he has also established a pattern of working and living as a dentist that he looks forward to being able to maintain for the next 25 years. He has never been happier. He is living like he is already retired.

Our ability to work and earn a living is called human capital. When our financial capital (i.e., savings) is small, we have no choice but to find a way to sustainably tap our human capital. We should also consider ways to reduce our annual expenditures without giving up the quality of our lives.

Thoreau wrote,

The cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.

Thoreau deliberately lived on less, working part time as a surveyor, so he could have his afternoons free for long walks, writing, and thinking.

If I should sell my forenoons and afternoons to society, as most appear to do, I am sure that for me there would be nothing left worth living for.

…

The man is richest whose pleasures are the cheapest.

We should ask ourselves, how can we live like we are rich, but without the money? In Mexico, I learned that a one-room house can feel just as homey and tranquil as a much larger dwelling. Now a one-room house might be a little too small, but a home or apartment with great natural lighting and a small footprint in a part of the country with a lower cost of living is certainly a way to live rich without the money.

So is owning fewer things, but of higher quality, that will last for years. The armoire in the Yucatan couple’s home was handcrafted by a local merchant. It was beautiful and will last for centuries. We can also focus on experiences and less on belongings. One doesn’t need monetary wealth to bask in the serenity of the woods or the beach.

Thoreau died at the young age of 45 with very little wealth. Yet I have no doubt he could have sustained his rich and freedom-filled life well into his sixties, seventies, and eighties. Our challenge is to find our own sustainable pattern of living and working that we can maintain for the decades ahead.

Works Cited

Henry David Thoreau, Walden, Ch.1.

Simplicity Collective, Thoreau on Working Hours.

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/205/205-h/205-h.htm

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!