Newthink Alchemy

For gold they say "Sun", for silver "Moon", for quicksilver

"Mercury", for copper "Venus", for iron "Mars", for tin "Jupiter",

and for lead "Saturn."

— Titus Burckhardt (References, p.77)

In the heat of the alchemical flask, liquid mercury vaporized (was released) to produce a purer form of the base ore. The alchemist called this distillation. He distilled saltpeter in alum to form nitric acid. In a corrosion-resistant vessel, he distilled sulfuric acid from alum. Fire made volatile materials stable and hard ones waxy, bendable, mixable.

This was serious business. Changing a substance into a solid, liquid, or gas; into a form more pliable or soluble; into jewel-like crystals, was more than transformation. It was transmutation, the alchemical term for the changes occurring as the "qualities" in the metal became purified through the chemical process (e.g., of distillation, coagulation, or dissolution). Transmutation allowed the impurities (dross) to escape and the metal to be released into its highest form, its essence.

And the highest essence was gold.

The true essence of lead is gold. Each base metal represents a break in the equilibrium which gold alone represents. (Burckhardt, p.47)

The cosmic correlate to gold was the sun, which mirrored the divine intellect. The earthly correlate to base metal was the human soul. The real goal was the transmutation of the soul into its perfect essence and union with the divine intellect.

This was not fusion; it was union — the divine intellect and the human soul shared some of the same properties and, therefore, mirrored each other. The alchemists often represented this symbolically in their crucibles as a mirroring of seeming opposites, as though there were a gravitational pull between them: downward and upward energies, lightness and darkness, sun and moon, gold and silver, male and female.

Scholars haven't decided on the etymology of the word alchemy; it probably comes from the Arabic al-kimiya (كيمياء, chemistry). But alchemical arts have antecedents in every past age and on most continents.

What is striking about medieval European alchemy is how extensive the metalwork actually was. The alchemists believed they were changing base matter, earth's materia prima, into purer, higher forms. Since gold was the purest metal, representing the spiritual/intellectual center of the hermetic universe, they set about to produce it in their laboratories.

The roots of European alchemy are Middle Eastern. In Egypt about 200 B.C., gnostic concepts found their way into the profusion of mystery religions coming from the East, from Greece, and elsewhere. The name Hermes Trismegistos, a combination of the Greek Hermes (Roman Mercury) and Egyptian Thoth (the "thrice-great"), was given to the “author” of these ideas, known as the Corpus Hermeticum.

The Corpus is a revelatory body of work, not a set of beliefs. Its adherents weren’t missionaries, but the opposite. Gnosis (knowledge) and transmutation were secret, protected beliefs and practices of coteries who thought of themselves as elite and more attuned to their cosmic origins than the average person.

Arab scholars brought the first alchemical texts into the West through Muslim Spain, probably as early as the tenth century. In the 12th century, an anonymous manuscript from Spain described a movement through the concentric spheres of space as an algorithmic ascent through a hierarchy

by means of which the soul ... gradually turns from a discursive knowledge bound to forms to an ... immediate vision in which subject and object, knower and known, are one. (Burckhardt, References, p.47)

The Umayyad caliphate in Spain (Al-Andalus) allowed the debate of religious ideas, and medieval scholars became interested in the hermetic writings. Their interest wasn't necessarily heretical. The symbolism was not unfamiliar to them, even though it was not an expression of the monotheistic faiths. Some speculation was accepted as a form of inquiry into mysticism.

At heart, medieval alchemy wanted to be a perfect version of its ancient predecessor. Perfection is the right term here. The belief that base metals have an inner essence, as we do, that can be refined, as our souls can, and that our refined souls mirror the divine intellect, was genuine. Mirroring is a primordial human need. One image it conjures for me is that of mutual gazing, like the mirroring effect between a mother and infant locked in a gaze that for the infant confirms its self.

The corollary to this idea that took place in the laboratory — the unusual preoccupation with physical transmutation — resulted in real advances in chemistry and the medical arts. (A friend of mine noted, on reading this, that without alchemy and astrology, and probably the Church too, there would be no modern chemistry or actual transmutation of elements in laboratories or precision cosmology, or the knowledge of the Big Bang.)

The Swiss alchemical physician and surgeon Paracelsus (1493-1541), whose work straddled the end of the High Middle Ages and the rise of the Renaissance, was a medical empiricist, but what drove him to find cures for diseases was his belief that we are composed of the same essence as the divine intellect, if only we could achieve it. The goals symbolized by goldmaking were the core of his work.

Abu Bakr al-Razí (865-925), the great Persian physician and astronomer, was an alchemist and the first person to produce sulfuric acid, an alchemical staple. His books and notes found their way into the west early and were a dedicated source of study for centuries. Like Paracelsus, he equated medicine with philosophy, and he wrote prolifically on medicine, alchemy, and astronomy.

The alchemists never did transmute the base metals. Lead is lead, and gold is gold.

Even so, alchemical symbolism was ahead of its time, astronomically. The golden sun was the radiating center of this concentric journey through the levels of hermetic intellect. The third-century B.C. Greek astronomer Aristarchos’s notion of a heliocentric universe, rejected in his time, was affirmed, in a way, in hermetic symbolism.

The symbol of the sun as cosmic center has even earlier origins. Philolaus, a fifth-century B.C. follower of Pythagorus, wrote that the earth, moon, sun, and planets all revolve around an unseen “central fire” (Philolaus, References). Even more interesting, Kepler in 1618 wrote that Philolaus may have believed in only one central fire that was our sun or that our sun mirrored, but that he used secret symbols to hide or protect such teachings from nonbelievers (Dreyer, References) — exactly what the alchemists did.

In its richness, alchemy combined otherworldliness with physical science. Immortality never materialized in the laboratory, but what stands out is the age-old yearning to experience eternity, whether you call it divine intellect, cosmic consciousness, everlasting life, or heaven, the reward of the faithful.

Alchemy Takes a Turn

As alchemical work advanced, rulers took notice. Cosimo de Medici sponsored the first translation (by Marsilio Ficino) of the Corpus Hermeticum outside of Spain. Kings and princes became "investors" in alchemical pursuits, patrons of those men who could turn lead into gold, prescribe cures for disease, and reverse the course of human aging. The focus on curing disease and extending life became goal-directed.

Thus in the Hermetic Triumph it is written: The philosophers' stone (with which one can turn base metals into gold) grants long life and freedom from disease to the one who possesses it ... this treasure has an advantage above all others in this life, namely, that whoever enjoys it will be perfectly happy ... and will never be assailed by the fear of losing it.

—Titus Burckhardt, Alchemy, p.29

In such patronage lurk some of the motives behind support for today's newthink alchemy, the preoccupation with similar goals through hoped-for technological miracles. Whereas medieval physicians were engaged with the mysteries of the body, the gnostic and hermetic traditions underlying alchemy actually abhored bodily reality. We were trapped in our bodies. Transmutation meant escape from bodily woes and aging.

“Transmutation” ... may be understood in several ways: in the changes that are called chemical, in physiological changes such as passing from sickness to health, in a hoped-for transformation from old age to youth, or even in passing from an earthly to a supernatural existence. ... Alchemy aimed at the great human “goods”: wealth, longevity, and immortality. (Multhauf & Gilbert, References)

Wealth, Longevity, Immortality

The quest for eternity and "the great human goods," as Multhauf & Gilbert called the alchemical prizes, has been ongoing probably since the first time someone looked up at the night sky, shuddered, and tried to make sense of what he saw.

Medieval mystics' descriptions of their ecstatic states have a virtual reality resonance. But as miraculous as these experiences were, they were still considered something humanly possible, albeit rare. St. Teresa of Avila (1515-1582) is famous for her vivid descriptions of her ecstasies, which arose naturally from her non-upgraded but gifted consciousness.

The alchemical newthink coming from some of the people working on the frontiers of technology today is not about plain old mysticism. They don't want the joy or mystery of apprehending the eternal in the temporal. They want the eternal, period.

And they want to be in charge of it. They want shortcuts — engineered evolution, neuronal brain implants, life beyond death via cryostatic biostasis, or better yet disembodied brains preserved and then revived and upgraded for life in space. Like their medieval hermetic counterparts, they don't like having to deal with a body.

Like the alchemists, they are getting a lot of notice by people in today's elite coteries, the princes and members of the 0.01 percent who dream the same dreams, and then some. Unlike the medieval alchemists, the modern ones have a more messianic than secretive style, even though their product is elitist. They are in awe of the golden calf they are constructing.

Interesting Times

There’s an old Chinese saying, May you live in interesting times. Well lucky us, we do. We scour the earth for remnants of our earliest ancestors, we want to resurrect the wooly mammoth, and we thrust ourselves into work on a future of engineered eternal consciousness that obliterates the earliest remnants and the mammoths and everything else from memory. With not a beat skipped.

Yuval Harari’s books, Sapiens (2015) and Homo Deus (2016), are a provocative romp through our ancient past and distant future. He is correct to remind us that we weren’t the only ones on the branch of genus homo, we had a few cousins.

I miss our cousins, the Neanderthals. I wanted them to be there in southern Spain when I visited a few months ago. We shared with them some of the most recent .00005 percent of the 4.4 billion years our earth has existed. We exchanged DNA. Who knows if we will last as long as they did?

They didn’t have algorithms for eternal life or visions of dystopian utopias. Neither did our “archaic sapiens” (Harari, Sapiens, p.26) ancestors tens of thousands of years ago, who spent their time putting a roof over their heads, hunting for dinner, and perhaps relaxing after a long day. Our “imagined hierarchies" (Harari, Sapiens, p.143) hadn't yet wreaked havoc wherever we went. Reading Harari's assertion that our ancient forager ancestors were the most knowledgeable and skillful people in all of our human history makes me downright wistful.

There is no proof that human well-being improves as history rolls along.

—Harari, Sapiens , p.241

The idea of "imagined hierarchies" needs a long, hard look. It's old news that we live as though some lives are more important or more essential than others. The alchemists were not immune to this idea, pursuing a secret knowledge to get an edge on the immortality front.

in 1870. Public domain image.

But it’s the face of Truganini, the last ever Tasmanian, that haunts me. As Harari tells it, she died in 1876 after seeing her people vanquished and was then photographed, dissected, and her parts curated in a museum. What was learned? We learned that people did that. That’s about it. No Tasmanian is alive who can tell us anything about Tasmanians.

I hope it’s not all our fault that there are no more Neanderthals. I wonder what it was like for our sapiens ancestors who lived near them. According to some scientists, we even lived in at least one of the same caves (Tabun Cave in Israel) that they did, about 80,000 years ago (Gibbons, References). The latest research on this topic says that the Misliya Cave in Israel shows successive periods of hominin occupation going back 180,000 years, with Neanderthals and sapiens living close together (Stringer & Galway-Witham; Herskovitz et al., References).

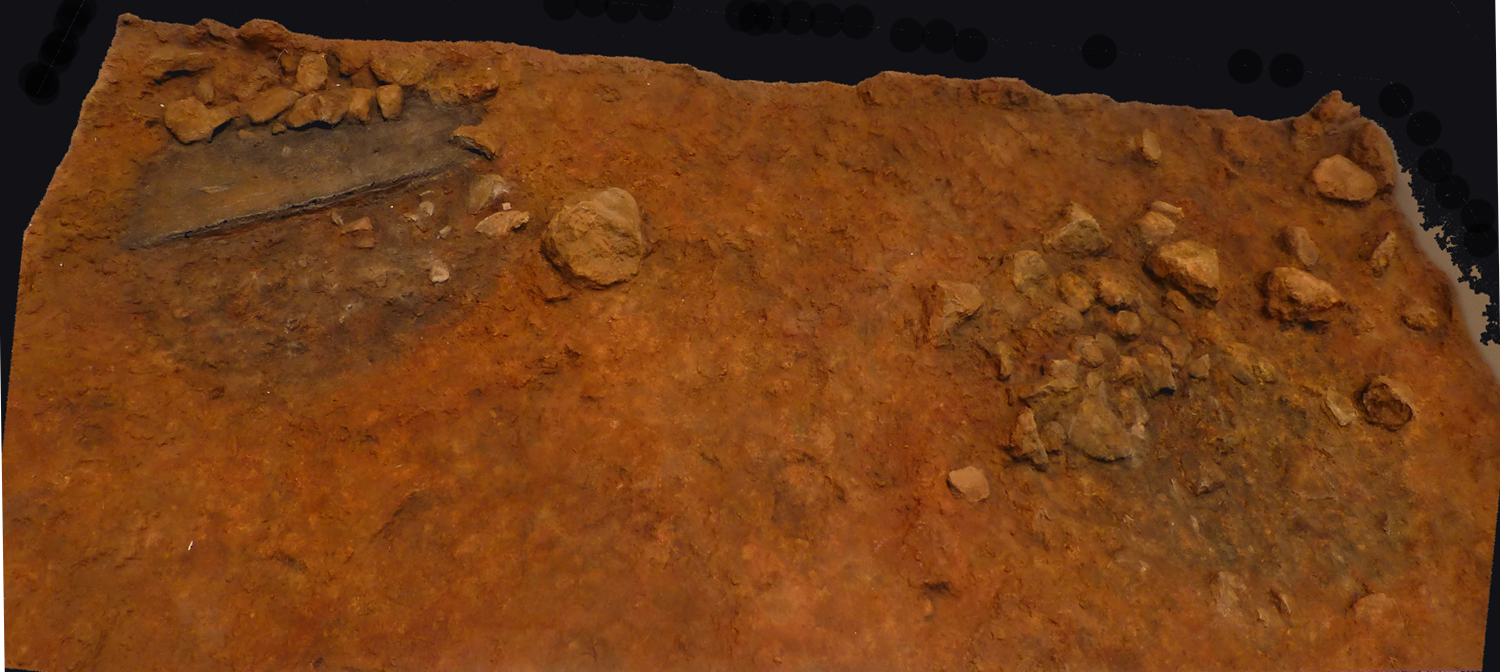

Look at the picture of the 228,000 year-old excavated hearth below. It was discovered at the Bolomor Cave, 60 kilometers south of Valencia, Spain. It is the oldest known fireplace in Europe, housed in Valencia’s Museo de Prehistoria. I saw it at the 2014 Venice Biennale for Architecture, where it had been lovingly transported and displayed.

Imagine — Neanderthal architecture! The information accompanying this hearth, provided by Josep Hernández Peris, who led the Bolomor excavation, stated that it shows evidence of butchering and cooking turtles, rabbits, and birds; of a stone tool industry; and remains of human teeth and bones. The stones and bones in this photo are original found objects.

The fireplace was important not just for heat, light, and cooking, but for socializing and planning, says Hernández. It was a family hearth,

... a core for activities and ... a spatial distributor. In this way it facilitated the development of an articulated language. When the hours of light were extended by the light of the fireplace, productive activity increased, time could be spent making work plans, distributing tasks, and favoring in general communication and the exchange of ideas. (Hernández, Venice Biennale, 2014)

Neanderthal scholars say these ancient humans not only had language and lived in extended family groupings, but that they cared for their elderly and sick, played with their grandchildren, buried their dead, and had lifespans, sometimes, of 70 years.

Some Neanderthal caves were cavernous, with several rooms, which scholars are excavating for evidence of special activity areas. The caves in the picture below, from the Gorham’s Cave complex on Gibralter, have a neighborhood-like appearance. Sea levels were much lower 200,000 to 32,000 years ago, when these caves were occupied; they had a two-mile-long shore before they met the water.

Neanderthals didn't leave us symbols or cave art, just their caves, but we carry in our genes the same sensations, feelings, and responses to circumstance that they had.

(An article in a recent issue of Science Magazine suggests that Neanderthals did make cave art. Using uranium-thorium carbon dating, scientists have dated the art in three caves in Spain to before 64,000 B.C., the oldest dated cave paintings in the world. See Hoffman, Standish, et al., References.)

Newthink, Oldthink ...

Research to provide sustainable environmental conditions or good health for the planet and its inhabitants is nowhere near the top of the newthink totem pole. It is crowded with esoteric and elite interests that even newthinkers can't keep up with.

Alas, there is nothing new in newthink alchemy. There is new technology, but the thinking is very old. This is a problem, putting old thoughts into new science. The idea of living for hundreds of years or participating in cosmic life away from our planet not only isn’t new, it also isn't necessarily creative. It may even be escapist, in which case the search will feel false. And if you search too hard you could miss all the good things in life.

As the newthink alchemists give their lectures, publish their books, and go on their rounds of public debates (instead of spending their time doing research), they are gaining adherents among young people, many of whom are tech savvy but not the best judges of where to fit technology into life as it leaps along into the unknown.

People rarely appreciate their ignorance, because they lock themselves inside an echo chamber of like-minded friends and self-confirming newsfeeds, where their beliefs are constantly reinforced and seldom challenged.

—Harari, N.Y. Times Book Review, References

Extended Life — From Here to Eternity

The old demon lurks, the enticing idea that sounds plausible but isn’t. In an Intelligence Squared debate entitled Lifespans Are Long Enough, Paul Root Wolpe, a bioethicist at NASA, and Ian Ground, a philosopher, faced off with Aubrey de Grey of SENS (Strategies for Engineered Negligible Senescence) and Brian Kennedy of Buck Institute for Research on Aging.

Wolpe said that the debate’s title was misleading, that the debate was really about the post-human fantasy of living for hundreds of years. De Grey called aging the world’s most important issue (it’s certainly his), and he and Kennedy argued that our biggest challenge is to defeat the causes of aging before it ever begins ... and then, of course, the next logical step is extended life.

Wolpe and Ground both argued the difference between wanting to defeat disease and enjoy a healthy old age, versus wanting to extend life indefinitely and defeat aging altogether. But De Grey played the audience well, he stole his opponents' argument, saying he is only proposing that more and better research will help us all have longer, healthier lifespans.

When challenged that he has said in public that there is no reason not to live for a thousand years and that this is his real focus, de Grey waffled for a nanosecond before admitting, “Well, I might have said that ...” He never let on that he believed people must be convinced to submit to medical and technical interventions before they get sick. He wanted to appear as reasonable, and even more vital, than his opponents. He wanted to win the debate. And he did, by eight votes.

What is it like to live in a state of constant preparation for an extended life of hundreds of years? Are your routines centered around monitoring your nutrition, vitamin supplementation, physical movements, blood pressure and other bodily functions, diet, and exercise plan? Are you always on alert as to nearby physical or environmental roadblocks? An obsessive focus on self-preservation really is unseemly, and it is disingenuous to pretend to care about the rest of the world.

When asked what we'll do with our extended years, the gurus say something like, "There will be more time to experience life to the fullest" — more time with loved ones, more time for vacations with family and friends, for understanding all that life has to offer.

That's it? An eternity of dinner with friends and family?

Practicing medical doctors who have treated thousands of human bodies — brains, minds, consciousness and unconsciousness included — are not in the majority of the population investigating extended life scenarios. The newthink researchers need input from physicians in all the various specialties to learn more about disease processes — their onset, when they become recognizable, the variables involved in diagnosing and treating. Disease doesn’t necessarily favor age over youth. Talk to a neonatologist (newborn specialist).

Also, every body reacts to treatments differently. Setting out to extend life as an end in itself does not take into account the confounding variables of genetics, life style, level of family income, intelligence, medical intelligence (which Steve Jobs lacked), access to care, mental health, level of education, and a patient’s own compliance with medical recommendations, not to mention things like fear and denial.

Getting into subtleties, some bodies experience disease processes with no symptoms for a long time. Serious medical conditions like lupus, leukemia, and asymptomatic chronic kidney disease can present with an ordinary constellation of symptoms (a cold, e.g., or tiredness, a headache, a stomach ache). Diagnoses can be found incidentally; a physician looking at a suspected problem can uncover instead a hidden, life-threatening problem.

Physicists, who work with physical matter and are acutely attuned to the behaviors of the matter they work with, are also underrepresented in the extended life community. Mathematics may be the language of both quantum physics and computer science, but quantum mechanics more directly studies the natural world. Mathematical algorithms live in their machines, coming up with their predictions based on how the data is set up and their interactions with the new data constantly being fed to them. As for humans, the majority of us do not experience the world simply as a tiered or layered algorithm or the body as a mechanical or mathematical construction.

Engineered Evolution

What would you rather have? A diamond formed over millions of years 90 miles down in the earth’s mantle, thrust to the surface in a deep volcanic eruption, carrying with it the facets of its evolution? Or one created within a week via engineered evolution, in which graphite is subjected to intense heat and pressure to produce a gem that carries traces of the solution it was processed in? Are the two the same thing?

Most people don’t really think about things like speeding up human evolution. When I asked my neighbor, a gifted welder, if he ever heard of engineered evolution, he said "no." Still, for those invested in the effort, it can’t come soon enough. They don’t want to miss out on life in the future, but they don’t have the time to wait eons to get to it. Can we manufacture it?

On January 16, 2018, my local NYCTV Channel 22 aired an interview with Dr. Philip Kennedy, a neurosurgeon whose company Neural Signals fabricates brain/computer interface solutions to aid in the restoration of speech and movement to conscious patients who have lost these abilities — an impressive research focus. I hadn't previously heard of him, but the show was provocative so I researched his company on Google afterwards.

The televised interview wasn’t about his restorative work. Kennedy instead presented his wish to take his work into the public sphere, to use similar implant technology to enhance normal brains, in the developing field of artificial neural-networks.

There's a world of difference between focusing on a disease or disability, an injured patch of tissue, versus global enhancement of a perfectly fine brain, especially since no one completely understands how the human brain works (and there is nobody out there who will declare absolutely that they do know).

Kennedy told his interviewer that we should keep brain enhancement cheap and make it for everybody, so we won’t have to fear that governments or individuals will try to take it over. He didn't say who would be in charge, and his cost reasoning is based on fear — an unfree starting place for science.

The implants will be permanent. You can even implant them in your kids to get them into a better college. Not everybody will want it, he said, and we may have to accept that "the cyborg era" will still be governed by basic intelligence.

The cyborg movement for brain enhancement will let us keep up with AI. We don't have to fear that the robots will perform better than us (more dystopian fear). We still may not evolve fast enough to get ahead of them, in which case we must accept that an AI smarter than us is part of our own evolution.

It’s all in his book 2051, he said. We'll get rid of our bodies, use our brains, and go off into space. It's not science fiction, he says, it’s "science prediction." Our brains will be totally implanted. Like the medieval alchemists, Kennedy wants freedom from bodily constraints. His implanted brain will mirror the cosmic intellect, it's real destiny.

But the human brain's complexity, its sensory encounters integrated with memory centers for experiences, information, and feelings instantaneously, has evolved the old-fashioned way, over eons, and was already complex two hundred thousand years ago when our ancestors were making dinner alongside their Neanderthal neighbors. Our brains don't want to be AI.

The interviewer asked, does such a future deconstruct all that makes us human? Kennedy said we’re evolving, so sit back and accept it. In a different interview, he said:

We may be barely recognizable as humans. Of course, those that cannot afford or refuse enhancements will be another class of people. This differentiation will lead to huge social problems. But that is for the future generations to solve. The progress of technology is unstoppable .... ( Interview with D. Hoffman, References)

Unstoppable, or "technically sweet"? Sit back and accept it? Leave the problem parts for others? There are no new thoughts here and no good enough thoughts. We'll perfect ourselves by getting rid of ourselves. It reminds me of a phrase used in the Vietnam war, "We have to destroy the village in order to save it." Someone else can clean up.

This has nothing to do with medical research, with finding cures for vexing diseases that kill otherwise energetic people who really want to live.

In Belize in 2014, Philip Kennedy heroically underwent surgery to have a neuron recording implant put beneath the surface of his own brain, making himself a guinea pig in his own research. Recovery didn't go well. He had seizures and language problems and later had to have the device removed. He doesn't think he'll try it again. (See Daniel Engber's piece on Kennedy's surgery in Wired.com.)

Beyond Death — Total Immersion

When I was a child in school, I was taken by the seeming mystery that glass was a liquid. Made from sand. I would peer at different types of glass, looking for the striations that gave away its liquidness (I found them.). The Romans had a lot of sand and made beautiful glass, I thought.

Vitrification is the process of rapidly cooling a liquid to a state neither liquid nor quite solid: glass. The hazardous waste industry today uses this process to turn liquid radioactive material into glass, which makes it safer and easier to store.

Vitrification is an old word, with an alchemical ring — like dissolution, coagulation, elixir. It evokes odors, dark spaces, sealed chambers. The Historical Metallurgy Society has a datasheet (see Bayley, References) discussing the effects of vitrification in medieval crucibles on the gold, silver, copper, tin, and other metals found within them.

Vitrification is also the first stage of cryonics, or cryogenic biostasis, the effort to preserve people who have been pronounced legally dead and resurrect them sometime in the future (which may be in 30 years or 300 years).

As soon as possible after being declared dead, the "patient" is rushed in ice to the life extension facility and procedures start immediately. After CPR produces a heartbeat, doctors and technical staff assess brain swelling by drilling small holes into the skull. They open the chest (quickly cut right into it, as time is of the essence), check the heart, and start hooking up the veins and arteries to machinery that removes the body's fluids. The fluids are replaced with cryoprotective agents that will vitrify the cells and organs —put them in that niether liquid nor solid (i.e., glasslike) state that holds everything together and prevents ice formation during freezing. Then:

The body is placed inside a protective insulating bag and then inside a cooling box where liquid nitrogen is fed in at a steady rate. This takes place slowly, over several days, until the body reaches a temperature of minus-200 degrees Celsius. (Meera Senthilingam, References)

Glycerol, dimethyl sulfoxide, and dimethylacetamide are some of the cryoprotectants used in the process. These agents are normally used to preserve human organs for transplant surgeries. The hope for cryonics is that they will also be able to protect an entire body. Of course, organs for transplant have a short shelf life (often only an hour); nobody knows how a whole body will respond over 100-plus years.

The Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Scottsdale, Arizona, one of only three or four facilities in the world offering this service, calls the storage life suspension, a nice term for it.

And thus our "imagined hierarchy" continues its journey. While this process provides hope for the committed, it evokes the mummification and preservation of the Egyptian pharaohs, the guys at the top.

With no clue as to the revival outcome, the life extension advocates have a complete dependence on people who won't even be born for fifty or a hundred years or more. Will those future researchers and doctors be excited about working to revive the limbo set? Will they be amused by this old-fashioned attempt to preserve dead tissue? Will their technology be incompatible for revival purposes?

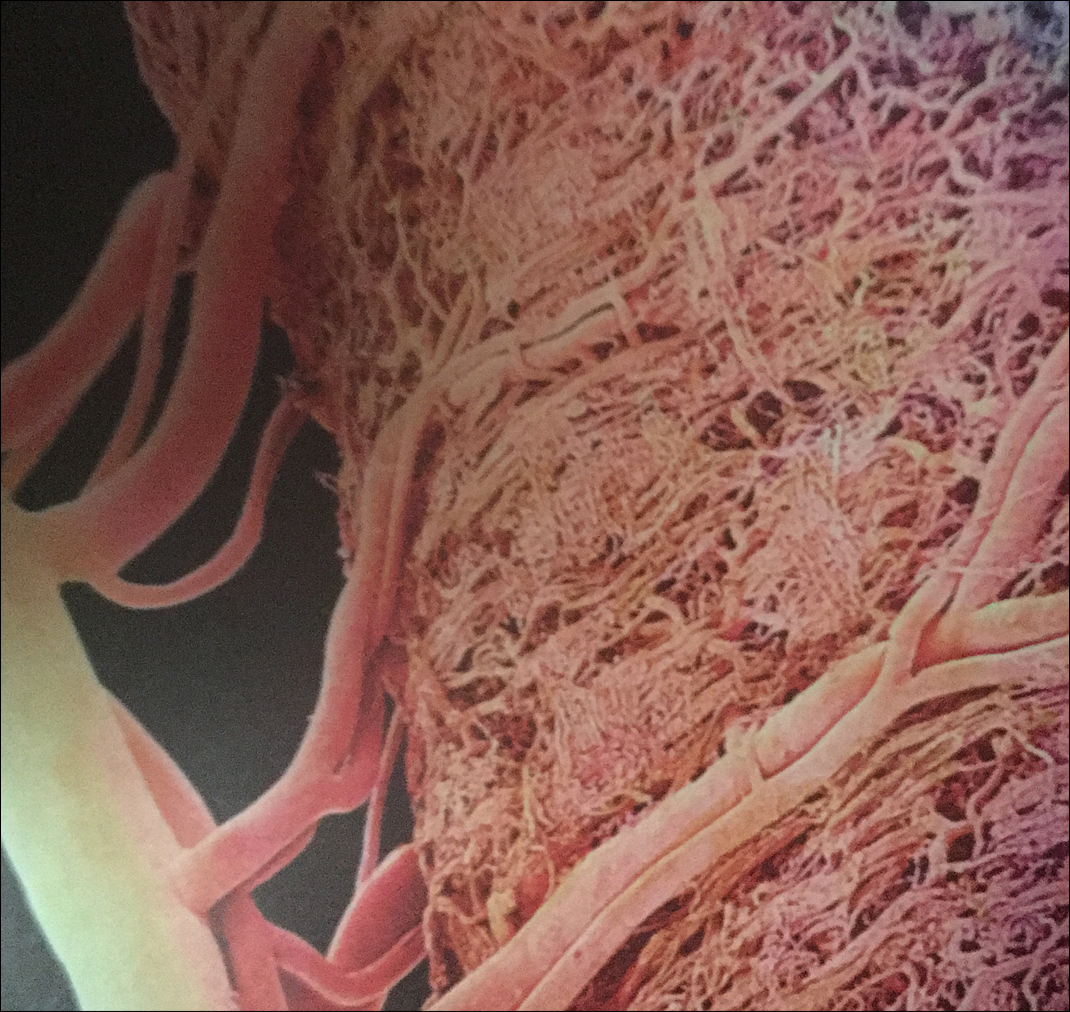

The thing is, while arteries carry oxygenated blood from the heart and veins carry deoxygenated blood back to the heart, at tissue level there are no arteries and veins. There are only capillaries. They are the smallest of the body’s blood vessels, tiny membranes thinner than a cell. They act like little sieves to let out white blood cells and immune modulators known as cytokines (which build or break down inflammatory responses to what's going on in the tissue), and carry in other immune cells, waste material toxins, and germs. Does just replacing the artery and vein fluid miss the point? What happens to the fluids in the capillaries? Is there any science as to whether the capillaries will be viable on revival, or will function like they're supposed to?

We must give the Alcor "patients" some credit for giving their bodies over to medicine and science. We don't know how future researchers may use their bodies. The suspended likely will not be returned to their former selves.

How do you mourn a suspended loved one? Mourning is a most natural human experience. You can’t get over a loved one's death without going through it. All great religions recognize this need. How does a family mourn the death of a person suspended in liquid nitrogen because they're planning to wake up again, long after their family is gone? I'm sure it's all worked out in legal and personal agreements, but it asks for the unknown and the strange.

Biohackers, Unite!

Most people embrace technology for its perceived benefits to them. But there is a mindset for whom technology seems more like a replacement for life. We've all heard it said that some people "think like a machine." Human behavior specialists say this group is in the minority (in the technology sector as well), with deficits that make them nonresponsive to certain human experiences that most people consider universally human. This is not a simple lack of empathy or awareness; physical proximity to others can be problematic for them.

In his new book To Be a Machine (see References), the writer and educator Mark O’Connell talks about his travels through today's transhumanist subculture, which he describes as "a liberation movement advocating nothing less than a total emancipation from biology itself (p.6)."

I was taken with his account of a group of young men he met in Pittsburgh who run the Grindhouse Wetware site, biohackers who call themselves a cyborg team working to "augment humanity with safe, afforable, open source" implant technology. Some had various lower level devices implanted in parts of their bodies as part of their research (automatic door openers, for example, so you can open your door with a wave of your arm).

O’Connell listened in on an NPR interview they gave. Here are some of their comments:

Far as I’m concerned, there is no amount of optimization of this barely evolved chimp that is worthwhile. ... The hardware we do have is really great for, you know, cracking open skulls on the African savanna, but not much use for the world we live in now. (O’Connell, p.139)

We are deterministic mechanisms. The problem is, most people make the mistake of anthropomorphizing themselves. (p.141)

[I want] to become a being of such unimaginably vast power and knowledge that there [is] literally nothing outside of [me], nothing beyond [me], [so] that all of existence, all of space and time, [is] consubstantial with [me] ... (p.155)

I’m trapped here ... I’m trapped in this body. (p.157)

This is unnerving. It’s not normal to fear death or feel trapped in your body when you’re as young as the men O'Connell talked to unless, maybe, you’re deathly sick or grossly disabled. When I was in my twenties I was too busy living my life to feel trapped in my body.

Their message is not life-affirming. The more I read and listen to the videos of transhumanists, the less joy I sense. They are not joy bringers or joy sharers. It’s not part of the conversation.

The Event Chronicle 2017.

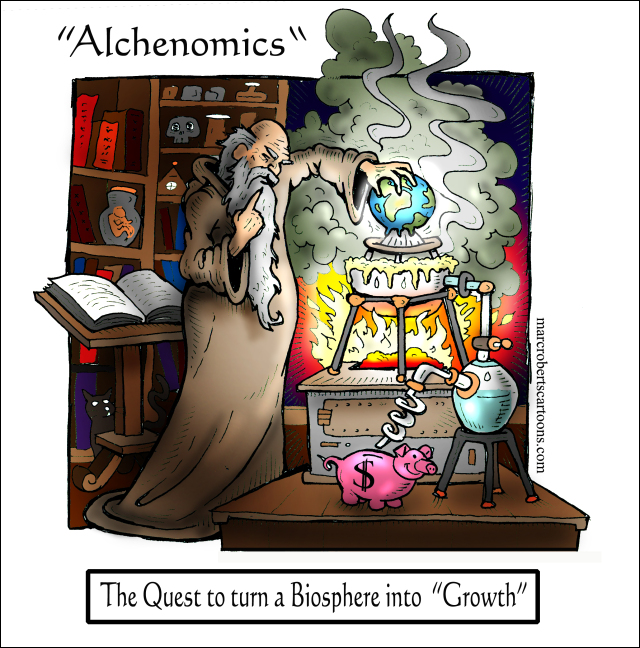

They want to be machines, but they haven't worked out either the engineering or the ending. Beings with cosmic consciousness floating through space? Who somehow retain their individual essence or perhaps memory? The symbolism isn't even as rigorous as its alchemical counterpart, which at least depicts specific events within a schema. Notice how in the image above, gold — the alchemical sine qua non — represents the desired state.

The website biohack.me is a carnival showcase of transhuman experimentation (implants, wearables, successes, failures). Another site, the Eternal Life Fan Club, depends on celebrity videos for its material and has very little technical material.

It's a Free Country, Can We Vote on This?

I never voted to have my right to privacy waived. It just happened. I can't buy a diet coke without that information winding up on a siren server to benefit a corporation, and I get nothing back to compensate the theft. Then I'm asked to work for the company as an unpaid volunteer and answer their questionnaire on customer satisfaction.

The insane pace of technology has forced more and more people around the world to think about how we should fit technology into our lives. Where does it belong? What should we ignore or get rid of? There are practical and moral issues, big ones.

We need more than expert discussion and opinion, though. We need nonexpert discussion and opinion. We need to hear from the people who, simply to get through their day, must interface with continuously changing and often confounding and unintuitive new technologies. In other words, we need research from the ground up. This is where you might pick up some real newthink.

In his book What Technology Wants, Kevin Kelly says that the traditional Amish, with whom he spent time, are not really against modern technology, they just require that it conform to their needs. This means that the Amish know what they need and how they'll use the technology they adopt.

- They are selective. They know how to say no and are not afraid to refuse new things. They ignore more than they adopt.

- They evaluate new things by experience instead of by theory. They let the early adopters get their jollies by pioneering new stuff under watchful eyes. (Kelly, p.225)

This doesn't mean they are backward. It means they control the decision making regarding their own needs. Nassim Taleb, not a Google advocate, advises as much in his writings and warns that if you don't know what's best for you, you'll hover uneasily above the bed of Procrustes, a portentous state.

We aren't the smart people we think we are. Take brain simulation. Our brain is still there, powerful as ever, after we make the simulation, and it will continue its role as power central very differently from AI, because the two are not really in competition. A simulation is not a self, brains are not simply data layers, and information is not experience.

We are more than the machines we make, not less. For some reason (I don't know why) we have an unnatural relationship to technology and its apparitions in modern life. We will never resolve the problems inherent in technological nanoweapon scenarios, for example, or criminal biotechnical experimentation (on animals or humans), if we don't first make some decisions about what is acceptable and what is not.

The fear comes from the technology sector itself, which irresponsibly has let its parameters extend without thinking, planning, or knowing what it was doing. “Hello world!” is dead. So we have to start being Amish about technology, we have to ask what it is in service of. Mark O'Connell makes this provocative guess as to why the tech sector has fears about its own powers:

[P]erhaps this fear of what might be done to us by our most sophisticated technology ... is a kind of sublimated horror at what we have already done to the world, to ourselves. We are already, many of us, controlled in ways we barely reflect on by machineries we barely understand ... (O’Connell, p.107)

The word robot comes from the Czech robota, meaning forced labor. It was coined by Karel Čapek in his play Rossum’s Universal Robots, or R.U.R. Forced labor. Think about that. Slavery isn’t acceptable these days, and cheap labor in far-off places is far from perfect. Robots answer corporate prayers — fewer employee demands and more forced labor, a win-win all around.

What Would We Vote On?

We could vote to take a breather from newthink alchemy and focus on better, more realistic, more appropriate uses for technology. We could vote against using technology in areas where humans do a superior over-all job. We could vote to pay a fee to use social media sites, if it would ensure privacy and fewer fake news stories.

We could vote to use technology in the interests of the majority. This might include better educational and medical care on a basic level, not just research on rare medical conditions. We could vote for better public education about how technology is used in the financial and business sectors and how successful we think our corporate use of technology actually is. We could ask interested nonexperts to sit in on panels that discuss bioweaponry like implanted robots in living creatures (insects, small animals) used as agents of war.

Steady State Manchester is a web publisher whose mission includes highlighting our increasing wealth inequality and financial instability "so that all can live well and within planetary limits." The editors asked the cartoonist Marc Roberts to come up with something that compared modern economics with the alchemists' claims of being able to turn base metal into gold. The cartoon below was the result.

It would also help if Silicon Valley turned down the volume on its newthink religions, showed a more realistic sense of what life on earth consists of, and treated AI as what it is, machine intelligence. The subjectiveness of research focused on creating technology for eternal life deflects away from acknowledging real human suffering in the world. At least traditional religions exhort kindness, whether or not you are a believer. The Catholic Church, for example, specifies “corporal and spiritual acts of mercy," such as feeding the hungry or visiting the imprisoned. Modern technology, on the other hand, can be merciless.

The subjectiveness also deflects away from the good research in technology and from the art of tinkering for its own sake. It has a way of diminishing, rather than expanding, human intelligence, culture, and mystery, trying to fit it into a box that can never really contain it. Tomaso Poggio, director of the Center for Brains, Minds, and Machines at the McGovern Institute at MIT, gave a short, very good talk titled Understanding Intelligence, in which he said that we are far from "solving" what intelligence is and that it is the greatest problem in science.

We have intelligence in recognizing others. ... We have intelligence in arithmetic. We have intelligence in language. Those things are often uncorrelated and they depend on different structures in the brain. I think [the problem of] intelligence is going to be like [the problem of] life. ... All these systems, like AlphaGo and Mobileye, are very intelligent, maybe better than humans, in narrow domains of intelligence. ... Actually nobody knows how to have a broad intelligence with common sense, etc., which I don’t know exactly what it is.

Poggio then lifted his hands in a shrug, shook his head, and said, "What is intelligence?"

It's mysterious. Newthink alchemy's efforts to engage it have not been proven to work. There are no shortcuts to engaging the cosmos, as any NASA scientist will tell you. Whether or not today's alchemists are on the right track, there are true, deep, serious, long-arching-in-time consequences to their work. It is well known that science progresses through failure.

What it all really makes me think is this: we have to start thinking about how to live better on this planet because this is what we have. It's our best interstellar spaceship, and it's a nice place to live, if we can keep it that way.

References and Works Cited

[Note: This list of books, journal and Internet articles, and videos is partial and reflects my most relevant references.]

Justine Bayley, Crucibles and Moulds, Historical Metallurgy Society, March 1995.

Titus Burckhardt, Alchemy — Science of the Cosmos, Science of the Soul, tr. William Stoddart (Baltimore: Penguin, 1967).

Nikola Danaylov, My Video Tour of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation, London: Harvile.

J.L.E. Dreyer, "The Pythagorean School," A History of Astronomy From Thales to Kepler (2d ed.), 44ff. (New York: Dover, 1953).

Daniel Engber, The Neurologist Who Hacked His Brain — and Almost Lost His Mind," Wired, January 26, 2016.

The Evolution of Consciousness, World Economic Forum Annual Meeting, January 31, 2018.

Adam Frank, Dark Matter Is in Our DNA, Nautilus|Cosmos, February 2017.

Ann Gibbons, "Close Encounters of the Prehistoric Kind," Science, May 7, 2010.

Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow (London: Harvill Secker. 2016).

__________, Questioning Our Human Future, World Economic Forum, January 24, 2018.

__________, People Have Limited Knowledge. What’s the Remedy? Nobody Knows. Review of The Knowledge Illusion: Why We Never Think Alone, by Steven Sloman and Philip Fernbach. New York Time Book Review, April 18, 2017.

__________, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (Harper, 2015).

Hermetica — The Ancient Greek and Latin Writings Which Contain Philosophic Teachings Ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus, ed. & tr. Walter Scott (1885-1925) (Shambhala, 1982) (reprint).

I. Hershkovitz et al., "The Earliest Modern Humans Outside Africa," Science, p.456, January 26, 2018.

D.I. Hoffmann, C.D. Standis, et al., "U-Th dating of carbonate crusts reveals Neanderthal origin of Iberian cave art," Science, p.912, February 23, 2018.

Intelligence Squared U.S. Debates, Lifespans Are Long Enough, FORA.tv 2018.

Hans Jonas, The Gnostic Religion (Boston: Beacon Press, 1958).

Kevin Kelly, What Technology Wants (Viking, 2010).

Albert Lyons, M.D. & R. Joseph Petrucelli II, M.D., Medicine: An Illustrated History (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. 1987).

Robert P. Multhauf & Robert Andrew Gilbert, in an entry on alchemy from the Encyclopedia Britannica that is part of a longer piece on alchemy by Alexander Roob, entitled "The Hermetic Cabinet: Alchemy & Mysticism."

Mark O'Connell, To Be a Machine (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 2018).

Svante Pääbo, Studying the genomes of living and extinct people, TED Global, July 2011.

Paracelsus: Selected Writings, ed. Jolande Jacobi (New York: Bollingen Foundation, 1958).

Philolaus, Pythagorean astronomical system (Wikipedia).

Adam Piore, To Study the Brain, a Doctor Puts Himself Under the Knife, MIT Technology Review, November 9, 2015.

Tomaso Poggio, Understanding Intelligence, MIT Technology Review, November 7, 2017.

Hendrik Poinar, Bring back the wooly mammoth, TEDx, March 2013.

Meera Senthilingam, What is cryogenic preservation? CNN, November 18, 2016.

C. Stringer & J. Galway-Witham, "When Did Modern Humans Leave Africa?," Science, p.389, January 26, 2018.

TEDBlog Q&A with Paul Root Wolpe, “You need to engage the ethical question all along the way,” March 24, 2011.

Paul Root Wolpe, It's time to question bio-engineering, TEDx, November 2010.

__________, Reasons Scientists Avoid Thinking about Ethics, Cell, June 13, 2006.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!