John Paul Getty Center

I believe that architecture has the power to inspire, to elevate the spirit, to feed both the mind and the body. It is for me the most public of the arts.

—Richard Meier, Getty Center architect, 2001

The Getty Acropolis:

Mountain Temples

The first picture below, taken at night, is the Acropolis in Athens, Greece, built circa 500–400 B.C. The second, taken as twilight pushes up through the sky, is the Getty Center in Los Angeles, built circa 1983–1997.

I can’t be in Los Angeles without stopping here, at the Getty Center. I alight from the tram that floats us on air up the steep and winding path, I start walking, and then it happens: my body is, I am, aware of being inside this network — of structures, angles, curves, widening vectors, trellises and pergolas with vistas, quiet empty spaces, stairs climbing the outside walls, tables and chairs awaiting on the mountain floor.

This place, which seems to rest against the sky, is tethered to the mountains and to the city below. It's not too airily high, it's weighted. It feels like it was always supposed to be here, waiting to have been uncovered.

for The New York Times

I never studied architecture and I think about it only intermittently, but I know when I am inside its fine intelligence. Years ago in the old Steinway Hall on 57th Street in Manhattan, I attended a reception for my friend Robert DeGaetano, who had given a piano recital at Carnegie Hall across the street. I could barely mingle at first because I was too alert to the rotunda’s effect on me. The space, and the objects in that space, vaulted ceilings, columns, arches, and the pianos, defined it as a special place of history and music. It was hard at first to just stand around and mingle.

At home in California's Santa Monica Mountains, the Getty Center, designed by architect Richard Meier, is like so many mellow temples on the Acropolis. This is what I’ve called it since my first visit there in the early 2000s — the Getty Acropolis. I had the same feeling visiting the Acropolis in Athens, so I know the feeling.

Not built on classical lines and with no central Parthenon, the Getty is classic nonetheless because of its combined beauty, balance, friendliness, and deference to its surroundings.

Photograph © Frances D. Stevens.

It’s not the art inside that pulls at me, the rare books, the world-class library, conservation and restoration facilities (though it’s all of these); it’s the architecture. The buildings move me around — the design, placement, and liveliness of the walls, walkways, balconies, stairs, levels, gardens, turns, and jaw-dropping views so integrally related to the city below, the sky above, and the mountains, the mountains.

Space: Spaces

I get lifted into the spaces at the Getty. First my eyes are surprised, and then they start seeking out the spaces, the interstices, my gaze jutting about from one angle or wall to the next to see what's around the other side. My legs follow along as my eyes move me from space to space. I'm aware that it's not the architecture per se, not simply the buildings, it's the spaces they make between and around them.

As I walk around, the same space opens up in different views, different angles, creating a cornucopia of art against the sky.

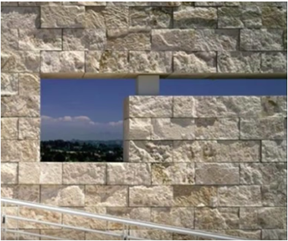

Where empty spaces exist in a wall, the architect is inviting us to look through to the views those spaces open up. Or, those spaces invite the view from beyond to come visit us. Where large, free-standing frames appear on the ground with no seeming structural purpose, we are being invited to go through, to cross a threshhold that will lift us, as it were, from one space to another.

Sometimes a structure that looks like a large stone or enamel frame juts out, hanging from the top or side of a building, hanging in space, catching our attention to its shape up there, so that the space in turn frames the shape. The architect is using the sky as a canvas — architecture as art. Other times, space itself is the whole show.

This kind of architecture is suggestive, subtle, not always stating a purpose outright because it's purpose is simply to suggest, invite, or inspire.

Mr. Meier has said:

Architecture is about making space. ... The Getty Museum is an example of a place where people come from all over the world to look at the art, but also to experience everything that's around it ... The spatial experience is what architecture is all about. (Meier, Time Space Existence)

As your eyes continue to wander, you start to expect the surprise views, enclosures, and play of spaces. Yet the liveliness is not random or disorienting. With all of the Getty's architectural exuberance, there’s an emphatic peacefulness here, where the design invites you to sink into it, and when you do, to stay awhile, live in it for a while.

In the picture below, the City of Los Angeles opens up through a gateway looking toward the Getty's Southern Promontory. The architect placed this gateway, this rectangular stone, enamel, and glass arch, as a reminder that the Center reaches out to the city, and the city reaches back. The brown, raw mountains of California aren't distant, they are an everyday part of Angeleno life, what you drive over going to and from work, or out to dinner — or to the Getty Center.

Photograph © Frances D. Stevens.

Photograph © Frances D. Stevens.

Photograph © Frances D. Stevens.

It's Always Complicated

Background reading to write this article included stories about the complicated person of John Paul Getty (1892-1976), the oil industrialist who made this place possible. Information about his life just seeped in on its own. Maybe it shouldn’t have, and I wasn't necessarily intending it to. Getty lived when moguls who mostly loved their businesses and ignored their families were not judged as they are judged now.

Mr. Getty had five wives and five sons by four of the wives, sons raised in four different homes without strong attachments to each other or to their father. Though Getty was hardly the only titan of industry with frayed family connections, there is more wear and tear in parts of the Getty story than in other stories of family-wrecking wealth.

Yet Mr. Getty was an indefatigable and long-sighted worker and learner, the first person to create oil fields in the Saudi Arabian desert. He was a shrewd buyer of art and early on he had enough of it to fill a museum. His private ranch house in Malibu, which he bought in 1943, became the first repository of his collection, with hours open to the public.

When it came to art, his inclination was always to share and educate. He established the J. Paul Getty Museum Trust in 1953 for this purpose.

Getty betook himself to England for the last twenty-five years of his life. He bought a grand estate, the 16th-century Sutton Place (about 35 miles from London), to which he transferred some of his art and lived like an English aristocrat.

But he wasn’t really to the manor born. He was an American, and while in England in the 1970s he involved himself in building a new structure in Malibu large enough to allow for museum-size crowds and worthy enough to be a proper background for his collection of Greek and Roman antiquities.

Getty had his new museum modeled on the Villa Papyri, which had stretched along the coast of Naples in the ancient Roman city of Herculaneum before it was destroyed by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. The Getty Villa stretches along California's Pacific Palisades. It is a sumptuous, beautiful museum. It just doesn't get inside me the way the Getty Acropolis does.

Trustees: Trust: To Trust

On his death in 1976, Mr. Getty left the bulk of his estate to the Getty Museum Trust. He never saw his completed Villa, but his body was returned to it for burial on a nearby bluff overlooking the ocean. Legal wrangles over his will followed his death, as you would expect with a fortune the size of Getty's, but conflicts were resolved by 1982 and in February that year the trust received its full bequest of $1.2 billion. The John Paul Getty Museum instantly became the most richly endowed museum on the planet.

The next year, the Board of Trustees successfully petitioned the court to change the trust's official name to the J. Paul Getty Trust, and it set about planning how to fulfill the wish of its benefactor. His wish? To use the money for “a museum, gallery of art, and library for the diffusion of artistic and general knowledge” (see the iris, References).

Trust. This old, great financial term is one I love for its simplicity and character. It used to be in many bank names (e.g., Bankers Trust Co.). You don't see it much any more. This word recognizes that a most basic human trust is what gives any transaction or agreement its value. Without it, without trust, there is no value.

Getty trusted his trustees to have the knowledge and intent to use his gift as he envisioned. His simple request and gift to others, to spread artistic and general knowledge, was one that allowed the trustees to approach their work imaginatively and thoroughly.

Photograph © Frances D. Stevens.

The trustees — and the scholars, builders, financial administrators, architect, landscapers, designers, and construction workers they employed — are heroes in this story. The trustees found themselves with the world's largest museum gift and almost no restriction on their imaginations for its best use.

They were honest fiduciaries. The trust's early years involved conflicting interests on the parts of many involved in its creation, but their collective eye was on their long-term goal. They created something that would take on a life of its own in its outreach, without straying from the gifter's simple wish.

Mr. Getty was lucky. Maybe he knew he was, knew that he had the right people to turn his gift into something extraordinary, but I think even he would be dazzled by what happened next.

What happened next was the Getty Center. In addition to the Getty Museum, with its dramatic stairway visible from the tram dismounting area, its entrance hall, its four pavilions and courtyard, the trust established the Getty Research Institute, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Foundation, all of which are integral to the work of the Getty Center.

The Research Institute and Library is used by scholars from all over the world and is considered by many the finest art library there is. The Conservation Institute restores art for the galleries, but it also does restorations in far flung places on several continents, from ancient stonework and archeological conservation to protection of artifacts in challenging environments. I cannot find the article online that I read in The New York Times years ago about the painstaking scientific methods the Getty's restorers use to bring old art back to life (and about what they discover in the process), but I remember thinking that New York doesn't have this kind of place, that Los Angeles has the best place in the world for art restoration and preservation.

The Conservation Institute also has a Web and Digital Initiatives group for database programming, multimedia design, and new technologies for conservation purposes.

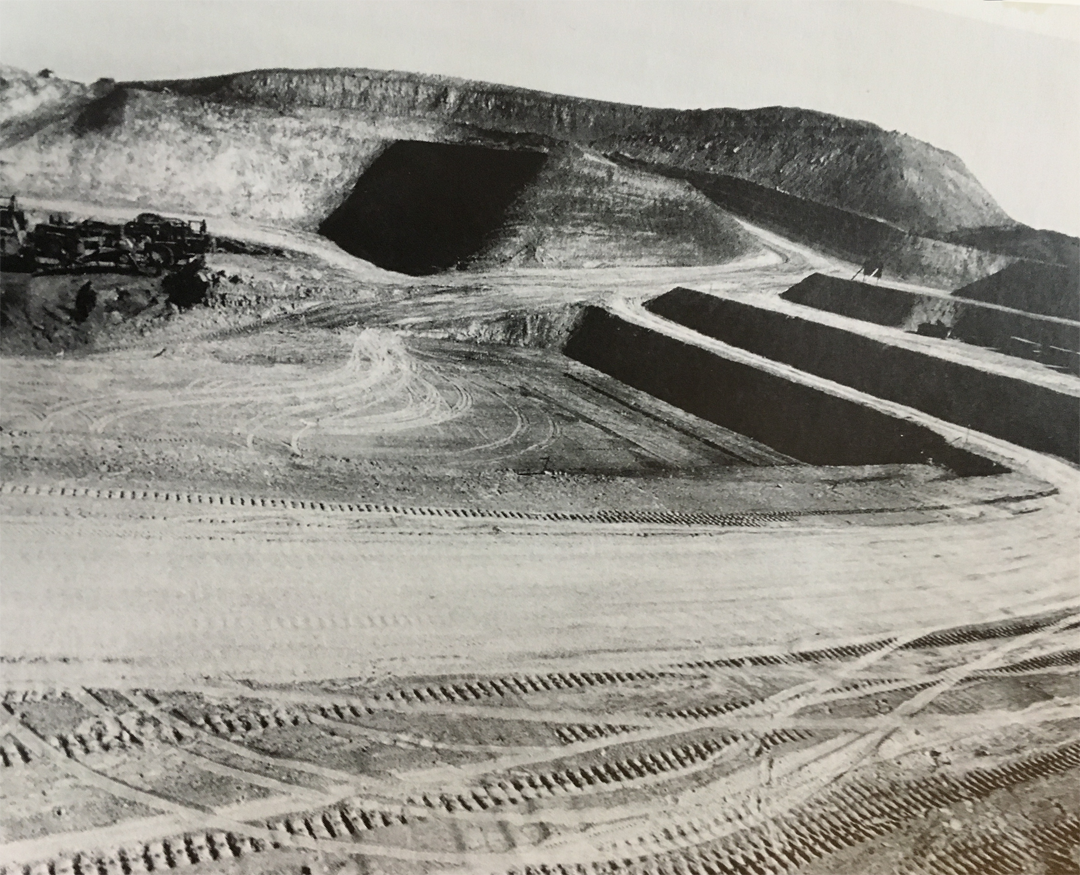

It's easy to take for granted that something just appears and then the public also just appears. The Getty Center didn't just appear. It was a 12-year construction job the likes of which the builders had never before seen. The engineering, the grit, required to plan and build this place, to get the job done, are a testament to what is doable. In the video below, one worker said that with just one road to transport tons of materials up the mountain, it was like constructing a building on top of a pinhead. (If the video screen below is blank, please refresh your page.)

Here is a general layout of the Getty Center. I superimposed the names of the main buildings on the Getty's own map.

Copyright © J.P. Getty Center.

Making a Place: Richard Meier

I've made many visits to the Getty Center over the years, but only recently have I read about the work of Richard Meier, since taking an official "tour" on my latest visit this past February. Meier is the New York architect commissioned by the Getty's Board of Trustees to design the Center. He had designed exquisite high-end houses, museums, and special-purpose buildings all over the world, but the Getty would top them all.

For this project, Meier sat for a long time on one mountain top (above), imagining shapes, structures, and spaces on the mountain top on the opposite side (below). He imagined how people would move about, and be moved about, by these structures and spaces. In his book Building the Getty, he wrote of the chosen site, "the movement of the contours was extremely vivacious, and the views afforded by different vantage points were unquestionably spectacular" (p.32, see References).

a basic framework takes shape. Photograph by Frances D. Stevens of p.81 of Richard Meier's Building the Getty.

The project involved not simply picking the site, but following a number of exacting rules set out by homeowners in the valleys below, especially by members of the Brentwood Homeowners' Association. The homeowners were worried about privacy, noise, the effect of years-long construction on property values, the changing view from their windows, and the unsightliness of too many tall buildings, among other things. They voiced their needs loudly and clearly, via legal representation.

The residents ruled against the use of white, Meier's favorite color. They insisted on off-white as a prevention against unwanted glare from the hill. They wanted parts of the complex to be completely hidden from their view by evergreen trees. They mandated a height restriction of 45 feet for all buildings except the museum, which they gave a little more leeway.

No building could be more than two stories above grade level, so Meier had to design downward into the earth to accommodate the spatial requirements of each building. All parking (seven levels), library book stacks, storage areas, and mechanical and electrical services had to be built underground. No part of the mountain could be removed; earth dug out from one area had to be put to use in another area. At night, there must be as little artificial light around the perimeter as possible.

How severe were these restrictions? On the one hand, they were set by people who lived there, people who knew that place over an extended time, its mountains, skyline, flora and fauna, sunrises and sunsets. While the restrictions were a challenge and I'm sure a surprise for the architect and trustees, they were based on the residents' experience and could be considered a contribution of sorts to what became the Getty Center.

On the other hand, the battle with the homeowners was a threat to the fulfillment of the trustees' obligations and Mr. Meier's artistic vision, which was focused on the same mountains, skyline, rising and setting sun, and flow of the landscape and people within it. The Getty is proof that engineering and artistic ingenuity, along with human cooperation, can overcome great odds.

Meier was not compromised. While none of the buildings are higher than two stories, they have a sweeping beauty and an impressive functionality. The engineering girding the entire place is as well thought out and as evolved as the design elements. The Getty crew even lived through the 1994 earthquake, which taught them a lot about the materials required to withstand another one.

Meier's ability to stay constant to his vision over 12 years of continuous redesign and renegotiation over planning, development, choice of materials and colors, and the inevitable structural issues that came up, all helped to give a sense of completeness and permanence to to the Getty Center, which might have been absent without the twelve-year maturation process.

It is never too late to learn new things. In researching Meier and listening to his interviews, I got a good review of modern architecture, its history, academic and structural antecedents, and influences all over the world.

I think a sense of of space, and of place, is innate. The "modern" style has been all around us for a long time. It defines much in our culture. To me, the Getty Center's uniqueness isn't simply its design, but how importantly this place connects locally and how far it reaches globally, from that local place.

Place. What does it mean, a sense of place? Some purists have questioned what, exactly, the Getty really is, because for them, philosophically, "local" excludes "global." The Center has even been described as schizophrenic for not providing a good enough explanation of how it can call itself local, when it works so hard to maintain its global reach.

Yet no one questions the local/global importance of New York City's renowned museums. What is the difference?

The Getty Center certainly serves a global purpose. Go to its website to see how far and wide its scholarship and conservation work extend. On my tour in February there was a young French architecture student, two Asian art scholars, a couple of San Fernando Valley residents, and tourists like me from disparate places. It doesn't work to be a philosophical purist, because the Getty Center is organic — a living, evolving, world-class institution that moves in step with the times.

The Getty is primarily local. The Angeleno sun is central to its design. Most important, it belongs to the City of Los Angeles. It was built in a space that exists within the city, in the Brentwood neighborhood. You can go to local concerts and dance performances there, hear a good lecture, and take in an exhibition of works by local artists. When what to do in Los Angeles is the question, the answer may easily be, "Let's go to the Getty." Here again, Mr. Meier's ideas about this are clear:

[M]y sense of why it is important is that it creates a place, a place that didn’t exist in Los Angeles. A public place, a place where people can come, they can experience the entire city in terms of the way in which they view it from that site. They can take part in the cultural activities which go on there, or they can just come to it, not as an amusement park but as a special environment in which to have lunch, to have dinner, to be with their kids, to sit in the gardens. ( No.22, Web of Stories)

Public. Meier is humble in discussing what public architecture means to him. A building's design is never an end in itself. A building is not simply an object in space or an assemblage of design elements. Public architecture exists in the service of people. Not only the buildings, but the spaces around them are inhabited by people. The user friendliness of both should be the first consideration.

Meier has said that his small-scale work was good preparation for his later large projects like the Getty. A small-scale work requires “maniacal” attention to detail; every single element is part of the whole. At the Getty Center, each structure is replete with its own details, attended to maniacally, and no one building predominates because each is a part of the whole.

The Center and its surroundings provide the space for each element — each building, walkway, plaza, stairway, etc. — to move us around. This sense of the smaller within the larger helps move you from one part of this place to another.

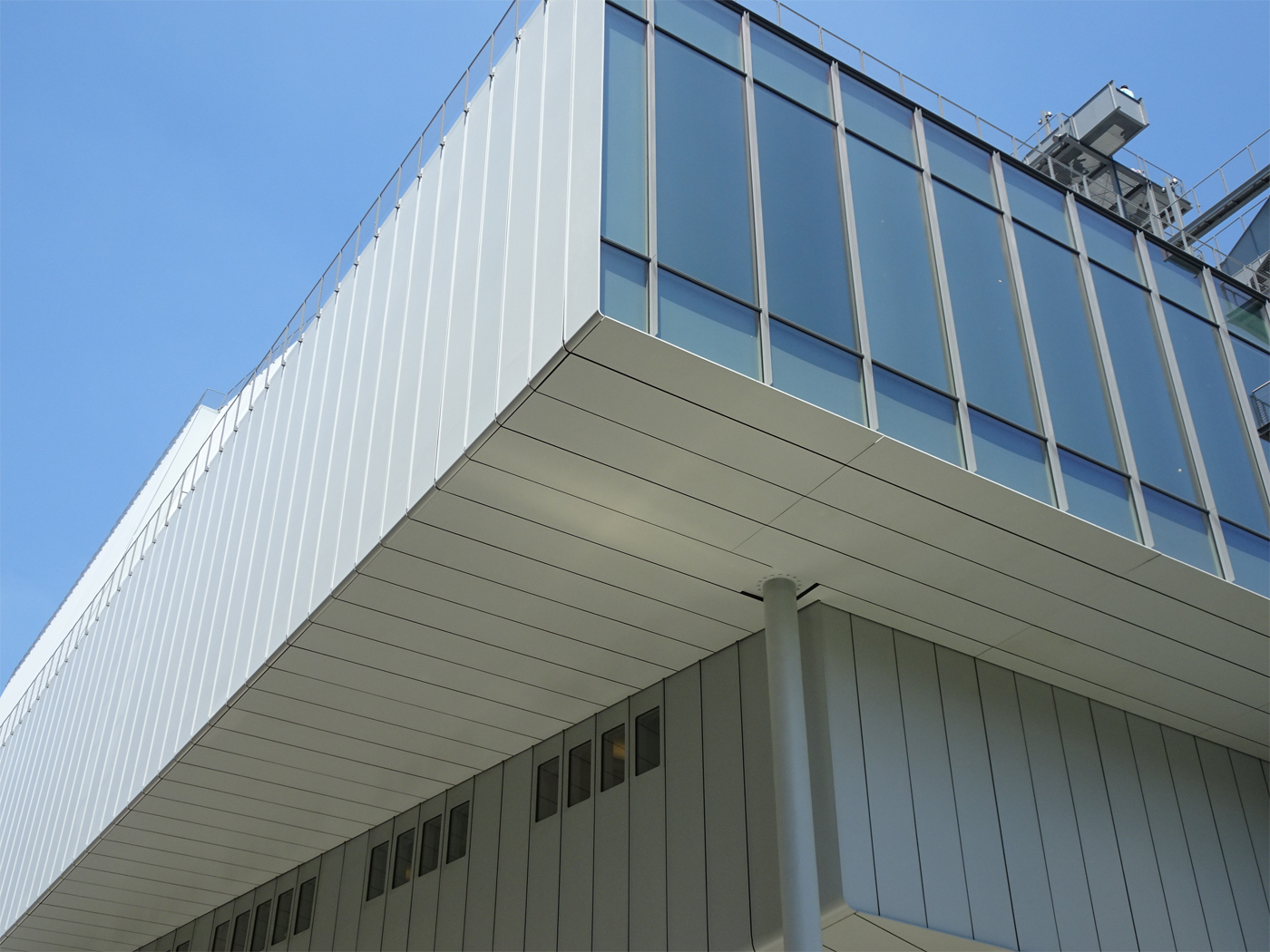

Lightness, space, human scale, promenade and ramps for moving through space — how do you move through the building and see the landscape? The building frames views. (Meier, No.10, Web of Stories)

Frances D. Stevens.

Frances D. Stevens.

When I drive up and down the West Side Highway in Manhattan, I'm aware of being at times next to a wall of glass. If I'm stuck at a red light, I sometimes use my phone to take a picture of a building that interests me. I took the picture on the right at a red light on my way to Brooklyn. The billowing angles and lowing whiteness were eye-catching. I didn't know who designed the building or that it was considered "postmodern"; only reading up on Richard Meier did I learn that it is Frank Gehry's IAC building.

In the Whitney Museum, the upper stories of which I also snapped along the West Side Highway, Renzo Piano has incorporated Meier's essential element for public places, user-friendliness. This place is a marvel of light, levels, hallways, and balconies; of city, river, and highway views; of friendly seats for tired feet, all next to the Highline, for strolling nearby.

Parts of Manhattan teem with interesting new buildings. Many, like those I pass on the West Side Highway, are glass and steel constructions, some clasically modern and others more adventuresome. These buildings by necessity must share space with one another and with their older neighbors. Manhattan, in its gothic intensity, accommodates them well while still taking care of its early historical buildings, many of which sit on dense little streets, especially around its lower end. Stone Street, for example, is practically medieval.

The combination of old and new works well in a place where it would be expected and enjoyed. It's unthinkable, for example, that Fraunces Tavern, the colonial tavern George Washington frequented that has been in operation since 1762, would not share a neighborhood with the new and very modern Freedom Tower and 9/11 Museum (Childs, Libeskind & Gottesdiener, architects), because both are rooted in the place that is lower Manhattan — rooted emotionally and historically in this place.

Still, Manhattan requires a certain determination on the part of both the buildings and their observers to be seen and loved. It's easy, walking quickly, to miss a perfect gem. There just isn't the Getty Center's luxury of surrounding space.

White, Light & Shadow

In the Global Art Affairs (GAA) Foundation video Time Space Existence, Mr. Meier talks about his love of white. It is all around us, everywhere we look. It reflects nature, makes us more aware of all of the colors in nature. It refracts light. "[W]hat people want where they live is space and light" (No.25, Web of Stories, References). In his acceptance speech for the Pritzker Award for Architecture in 1984, he said about white:

It is the color which in natural light, reflects and intensifies the perception of all of the shades of the rainbow, the colors which are constantly changing in nature, for the whiteness of white is never just white; it is almost always transformed by light and that which is changing; the sky, the clouds, the sun and the moon.

. . .

It is against a white surface that one best appreciates the play of light and shadow, solids and voids. . . . mine is a preoccupation with light and space; not abstract space, not scale-less space, but space whose order and definition are related to light, to human scale and to the culture of architecture. Architecture . . . describes space, space we move through, exit in and use. I work with volume and surface, manipulating forms in light, changes of scale and view, movement and stasis. (Pritzker Acceptance Speech, References)

The Getty Center's neighbors may have sold themselves short in deciding against white as the predominant color of their new neighbor. They might have enjoyed some stunning play of light and shadow in the hillsides.

Despite the rule against white, it is alive throughout the Getty. White and its complement, natural light, illuminate the underground stories in the Center for the History of Art and the Humanities. To access natural light underground, Meier installed a massive cylindrical tunnel (photo at right) that shoots straight up through the center of all six stories, open to the sky, "yet twisting into the ground like an enormous, shiny screw" (Forgey, References).

Whiteness and light flow through the Center's ceilings and extensive glass walls. Meier also used it inside the Getty's 450-seat auditorium and in outdoor spaces not visible from the museum's exterior, such as the Rotunda in the Museum Courtyard, also pictured here.

The California sun is a dramatic actor in the interplay of brilliance and shadow. The same wall may be blinding here, dark to invisible there, as the angles of surrounding structures meet the movements of the sun. Shadows are everywhere you look. The show is continuous, harmonious, and geometrically challenging to the eyes, like a puzzle, changing throughout the day in scale and view, ending in the soft contours of twilight. It's awesome.

Mr. Meier used 40,000 off-white, porcelain-enameled aluminum panels in the creation of the Getty. He also used expansive sheets of glass, in the walls, the ceilings, anywhere that allowed natural light to fill the indoor spaces or reflect the outdoor structures.

Travertine. He also used travertine, 1.2 million square feet of it. In the limestone family, travertine is a rough-cut stone found in diverse places around the world. The stone varies from place to place based on the geological characteristics of its origin. The travertine Meier chose came from Bagni di Tivoli, near Rome, the same quarry used to build the Colosseum in 70 A.D. and much else in the ancient city.

The stone has natural beige tones that in the white California sun have a flickering complexity. Its roughness, its tactile unevenness in the walls and columns, exude a warmth but also a rawness, which seems appropriate in the mountains. This stone from Tivoli, this travertine, also contains traces of fossilized leaves and small animals, eight to ten million years old. You can find them if you look close enough.

For the Getty, Meier had the stone split, guillotine-style, along its natural grain, so every stone has a partner stone whose split side is an exact fit. The texture provides a contrast to the smoothness of the glass and aluminum. This, and the stone's historical associations, indeed its fossils echoing an era that precedes the appearance of hominids on our planet, allow for an aura of cultural nourishment and permanence.

No mortar was used between these stones. They are set together by internal steel rods to allow for movement in case of an earthquake. This is a practical safety consideration, but the effect is to highlight the stones' natural beauty. The stones appear set in bold relief, the handiwork that went into cutting and setting them uncompromised by other materials.

Some Thoughts About Space & Place

There is much I didn't even touch on in this article, notably the art space itself. The Getty Museum is comprised of four separate buildings connected by a central courtyard, proof of the importance the Getty attaches to its exhibitions. Nor did I discuss the interior architecture, its spaciousness, winding stairways, glass dome ceilings, natural indoor lighting, and the trustees' many artistic and engineering considerations, such as the air temperature control systems, that make both the maintenance and the viewing of art an optimal experience.

I didn't mention the landscaping, although some of my pictures in the carousel below are of the Sculpture Garden, Cactus Garden, Central Garden, and the flowers and shrubbery on the grounds. I have been mostly taken by the architecture.

Philosophical ideas about space were not primary for me. My reactions to the architecture are spontaneous. However, Meier's book, his lectures and talks, inspired me to read more about ideas of space and place as they relate to the structures we live in and relate to.

Based on important factors, a sense of space, its interpretation and meaning, is not universally the same for all people. The same closed-off space that seems cozy to some seems restrictive to others. A wide open space feels freeing to some but overwhelming to others. I love to think about cosmic, deep space; for my close friend, it's just too far away.

In his book Space and Place (see References), the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan describes the many kinds of spaces we inhabit — mythical space, experiential space, the homeland, spaciousness and crowding, the body in space, among others. In his chapter on architectural space, he notes that the human being's awareness and experience of his environment, our ability to think and to give meaning to forms and shapes, is what guides the building process.

At the start, the builder needs to know where to build, with what materials, and in what form. Next comes physical effort. Muscles and the senses of sight and touch are activated in the process of raising structures against the pull of gravity. . . . Completed, the building or architectural complex now stands as an environment capable of affecting the people who live in it. Man-made space can refine human feeling and perception. . . . A planned city, a monument, or even a simple dwelling, can be a symbol of the cosmos. In the absense of books and formal instruction, architecture is a key to comprehending reality. (Tuan, p.102)

Meier and Tuan agree that architecture and the space it inhabits and surrounds should be built to a scale relatable to people's lives. Even a monument must be placed in human service, and when it is, it can act as an aid in our understanding of the world as a place for us to inhabit.

The slideshow below of several of the photos I took over many visits to the Getty is not annotated; the images just flow, one after another. If you intend to download one or more of the images for any reason, please include my copyright information. Thank you very much.

It is important to recognize here that recently, sexual harassment charges have been brought against Mr. Meier by women who have worked in his firm. In my reading up on Mr. Meier, it was hard not to come across this information. Should it come as a surprise? Yes and no. Yes, because you're thinking about the art and the work. No, because the intelligence and integrity of the work is a separate matter from the internal life of the harasser. I don't think there's one reason powerful and nonpowerful men (and women) impose themselves unwanted onto others; there are a number of reasons. We live in rocky times. I am glad, however, that within the rockiness is the exposure of this deep problem.

References and Works Cited

Eric Doehne, Travertine Stone at the Getty Center, The Getty Conservation Institute.

Cecilia Dougherty, The Irreducible I: Space, Place, Authenticity, and Change (New York: Atropos Books, 2013).

Benjamin Forgey, "Getty's Big Address," The Washington Post, December 14, 1997.

The Getty Center Design Process (pdf).

The Getty Center Facts (pdf).

Getty Museum Endowed, This Day in History, Februrary 28, 1982.

the iris (Getty Center blog), November 2, 2016.

Kristin Hohenadel, "Charting an Architect’s Obsession With White — and Other Fun, Irreverent Infographics," The Eye: Slate's Design Blog, August 27, 2015.

Blair Kamin, "An Art Acropolis," The Chicago Tribune, December 7, 1997.

Michael Kimmelman, "The New Getty, Dream and Symbol," The New York Times, December 16, 1997.

Richard Meier, Building the Getty (Alfred A.Knopf, 1997).

Richard Meier, Introduction and Index to the Getty Center, 1997.

Richard Meier, Pritzker Architecture Prize, Acceptance Speech, 1984.

Richard Meier & Partners, LLP, The Getty Center. Visit this web page to see 20 stunning color pictures of finished Getty interiors and exteriors, plus impressively clear, well-delineated images of studies for the site.

Nicolai Ouroussoff, "Shining City on a Hill," Los Angeles Times, December 7, 1997.

Nicolai Ouroussoff, "Realizing a Utopian Goal in Center That Doesn't Cohere," Los Angeles Times, December 1, 1997.

Tuan, Yi-Fu, Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience (University of Minnesota Press, 1977).

Jennifer Kay Zell, "The Art of Perception: Robert Irwin's Central Garden at the J. Paul Getty Center," LSU Graduate Theses (December, 2007).

Smaus, Robert. "A Gardener's Getty," Los Angeles Times, December 14, 1997. This article is comprehensive on the Getty Center flora.

Comments? Please send your responses

on the site's Contact page.Thank you!